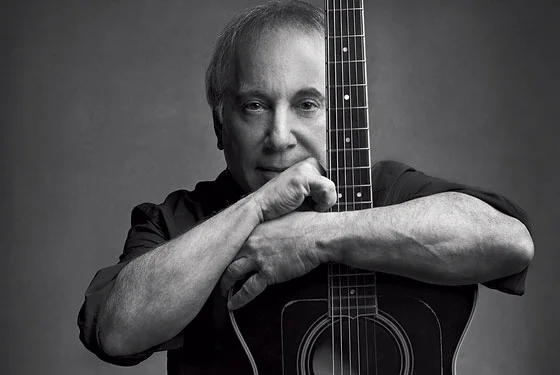

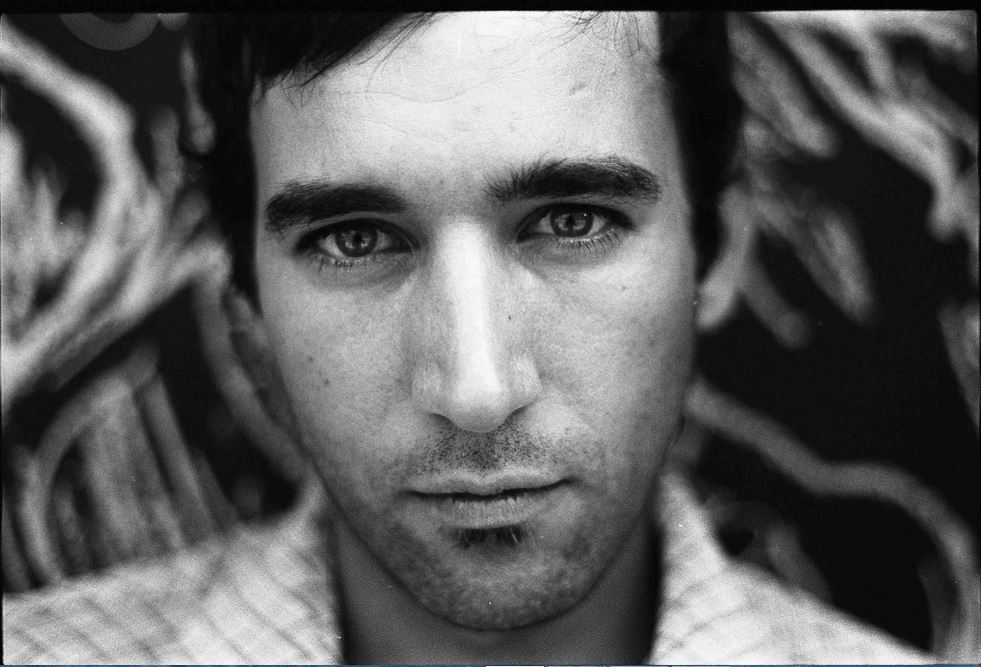

A while back, my profile on Micah Bournes was published on Mockingbird. Micah is a hip-hip artist, spoken word poet, and a blues singer. For a distilled look at his creative process, check out the original article. But there were many topics in our conversation that didn’t make it into the final draft, so I’m posting the entire, fascinating interview here. Enjoy it, and if Micah’s thought process resonates with you, his new hip-hop album, A Time Like This is due to be released in early January.

Hey, what's up brother.

Hey doing well, how are you?

Real good. Yeah man, Thanks for your patience. I'm glad we finally got to connect. I know stuff has been crazy for a minute, but I'm looking forward to this conversation.

Thanks for making it happen! I was just going to say that your album has been in my "heavy rotation" since it came out. It’s been one of those albums that I call “shower karaoke,” in that I sing along to it and really enjoy it, but than it sticks with you and causes a lot of thought. So thanks for your hard work on it.

Yeah, that's awesome man, I appreciate it. I'm glad it's been something that you've been able to engage with on that level. That's cool.

Oh yes, on multiple levels. It’s fun music.

I wanted to talk a little bit about the album process and how you've gone from spoken word poetry to this, and then I also have some questions on the book you recommended, Art and Fear. (I've given several copies away. I have some questions on how the themes of that book applied to this art making process.)

Man, I'm glad you read that too, because for me, when it comes to things that I've read, I don’t think anything has had such an influence on my creative process as that book

Really!

Just because it addressed so many of the hesitations and insecurity that I had and... well, I'll get to that. Let's get to the album first and then talk about that book, because I could talk about that book forever. [Laughs.] I suggest it to every creative I meet that's struggling. [I’m] like, "Read this book, read this book, read this book!” Yeah.

It's a powerful book. I bought a copy for a friend and I just bought another copy as a Christmas gift for another friend, so yeah. A little cottage industry of Micah Bournes recommendations are keeping that publisher alive.

How is the spoken word album creation process different from the blues album process?

Yeah, incredibly different. Well, I guess I'll just talk about how I got into blues from spoken word.

I see myself as a creative writer. [Yet] a lot of folks see me as a spoken word poet, and I own that, but when I started writing, it was not poetry. It was all hip-hop, it was rap lyrics. For the first two years I started writing [during] the freashmen year of college, so the first two years of college all I wrote was hip-hop. It wasn't until I was 20, my junior year of college, that I got invited to an open mic [event where] I saw spoken word live for the first time. I had seen it on YouTube but it wasn't until I was 20 years old that I saw it live.

And that's when I started writing poetry because I just really liked the environment of the open mic and how inviting it was for people to just share about anything. When I got into spoken word, it wasn't like I was going to quit rapping and just do spoken word. It inspired me in the same way that hip-hop inspired me when I fell in love with it. It was just like, “Oh man, I want to try that” because it looked like fun. And it wasn't like a career shift. I mean, it ended up being [one, but] it wasn't an intended career shift to switch from hip-hop to spoken word.

And kind of the same thing happened with blues. I had no intention of trying to shift from being a spoken word artist to [being a] blues musician. And even still, [now that] the blues album is out I don't know if I will ever do another one. It was just an idea. I got inspired.

The way that happened was I actually started listening to this band called The Black Keys. They are like modern blues rock type [band], but heavily blues [influenced]. I don't know if you have this in Canada, but there is this website called Pandora where basically you put in an artist that you like and they display other artists that are similar, and kind of help you discover new music and stuff like that. So I made a Pandora station and put the first input as The Black Keys. And it was amazing, because all of a sudden Pandora started playing all these old-school blues artists.

Now I had heard some of the names, [but] a lot of the names I hadn't. I didn't grow up listening to blues. My parents, they listened to a lot of kinda soul and funk but they didn't listen to blues [while I was] growing up. So I started listening and falling in love with all of these old school blues artists. It was something that caught my attention, because for a genre that I did not grow up listening to and had very little experience with, it felt so familiar. And I realised that was because blues came out of the black American tradition. And so I'm listening to these songs as I kind of ventured away from The Black Keys and [as I] listened to other blues artist I was like, "Man, the vocabulary they are singing, the stories they are telling, it feels so familiar!” It came from the Southern United States. My grandma’s from Mississippi, [so] everything they were communicating reminded me of my great-uncles and aunties and grandmothers and cousins. And so for someone who never listened to blues, I felt so at home. And it as like "Man!" So I just fell in love with it. And I just listened to it left and right. I was just listening to the Pandora station and so it's not like I knew a bunch of blues artists or nothing, but I would just let it play, all the time. I had a part-time job and every time I was at work I would put on this Pandora station.

Well, just like with spoken word, after a while of listening to it so much, I just thought, maybe I should… It wasn't even conscious [decision, but] when I would sit down to write, instead of rap or poetry, it would come out in a song, like in my head. I don't play an instrument, and [at the time I] didn't sing. So I had no intention of doing anything with these songs , I just started this because they were the ideas in my head, so I thought, “Why not get them out.”

But the writing process was very different. With both spoken word and hip-hop you have a lot of words per song. In a three to five minute poem you are constantly talking. And with hip-hop, a lot of it is flexing your lyral ability - turn of phrase, and metaphor, and double entendre. You're working with complex sentences, and structure, and poetic devices to make it beautiful in spoken word and with hip-hop. But with blues I noticed it was, number one, a lot fewer words per song.

A blues songs had maybe a third of the words that a hip hop song or a spoken word poem would have, even if it were the same length. A three minute blues song has so few words. But then [in blues you are] also pulling from a simpler vocabulary. You might still use metaphor, but it wasn't in the same way of metaphor on top of metaphor [and] complexity. Blues [language] was very common, every day language, [using] particular dialects [from] the African-American community. So, not only common [words] but specifically black kind of ways of speaking. So when I first started writing, I realised that [my initial] songs were too wordy because I had a background in hip hop and spoken word. It was really a discipline to learn; “How do I tell a story and create a world of art that's just as powerful as the way my spoken word pieces impact people?” But [doing so with] fewer words and simpler vocabulary.

At first I felt like I had my hand tied behind my back, but after a while [I realized that] it's not about dumbing it down, it's just being more intentional about your diction, about your word choice. You have to be precise, because you have fewer words, every word matters. And there are definitely times in spoken word pieces where I'm like, “I could have done without these sentences” or whatever, but with blues, it's like “You don't got that many words, you gotta make sure you do the right ones.” And so, yeah, that was a fascinating discipline. And then, another thing I noticed about blues is that there’s a lot of repetition. But it doesn't feel montanous or boring, it's just the way blues [are] repeated, it causes the messages to sink in in a different way. It's almost like I'm chanting it to you.

So yeah, man that's kind a how I got into it and then the recording process, was very different because…. What happened was, I didn't have any intentioan of doing a blues album. As a writer I just got inspired by the genre and started writing songs. But the songs on [‘No Ugly Babies’] were written over the course of probably four years. Because as I was writing them, I wasn't thinking about an album. I would just leave them because I didn't have a band and I didn't sing. I'd be writing poetry all of the time, and then every now and then, every few months, [I’d write a] blues song. They would just be on my computer.

After about three years I was like, “Man, I have about 15 songs.” Then I went on tour with a band, doing poetry, and I met this guy who was a musician and a producer and we start talking about music. He's telling me about how he loves The Black Keys and how he loves blues rock. And I'm like “Dude, I love that stuff!” So we became good friends, and then by the end of the tour I thought to myself, “Hey, if there is anybody…” Because he had showed me some of the other work that he produced. So I said, “Hey man, look, I got all of these blues songs. I don't play guitar. I don't really sing, but I think they are good songs. So maybe if I showed you them and you like them, maybe we can collaborate and we can bring these things to life.”

So he said, “Sure, send them my way.” So I basically recorded myself singing them, with no music, just me singing out the melody. I sang them onto my phone and I emailed him all the files. I sent him 13, no proably more like 15 songs of just me singing. Me like, "I don't pay no mind to no hate", like just like that. And so he listened to them and he responded; “Man, I really like these songs! We can defiantly make this happen.”

So it was very different from my spoken word album, because with a spoken word album I just worked with one person primarily; my hip-hop producer. A lot of hip-hop sounds - although some hip- hop definitely does incorporate live instrumentation as well - with a lot of modern hip-hop it's the beat or most of the sounds are either samples from preexisting recordings of music or are generated off of computer programs, or they're electronic sounds that are pre-recorded and just dropped in. And so even though a lot of the poetry albums that I've done have full music behind them, it was all done - with the exception of maybe one or two - it was all done by one producer and so it's just him putting in all of the sounds electronically.

Well, with this blues album pretty much all the songs - there might be one or two songs when we used programming, with sounds that we added to it. But all of the songs are live instrumentation. And with the exception of the one that's just the guitar, they all have at least 3, sometimes 5 musicians on them. So that process of working with, you know, people and real musicians, as opposed to one person who is dropping in a lot of sounds from a computer, was very different. We had these ideas in our head, and maybe a general melody, but then the drummer brought his personality to it. The basest and the keyboard brought her personality to it.

So we had these ideas and we are incoperating all these folks and we're like - oh, this sounds different then how I thought it was going to sound. Sometimes better, sometimes no, I don't like this. Whenever there's more people involved there's more things to coordinate. More things that need to happen. But at the same time, you also have more creativity, more perspectives, and so it… felt much more collaborative than my spoken word albums. They were collaborative too. But then there were [only] two people, me and the producer.

With this [project], even things like having background vocalists. You never need background vocalists for poetry, even if there's music. All of a sudden, I'm like singing with my friends. I have three voices on this song. On “Happy As Can Be”, I have a whole choir. A lot of the songs have background vocalists. Before, I never needed to ask my sister, or my mum, or my brothers to come in, because you don't recite poems together on a spoken world album. So like wow, my family is coming in the studio, my friends are coming in the studio, I'm reaching out to musician friends of mine that I knew they played but I didn't have the reason to collaborate with them before, so my buddy Joe played keys on a Four Left Feet, my homie Jackie played keys on Bo Boy Clean, Liz Vice sang on three of the songs. So it really felt collaborative in a way that spoken word hadn't been for me. Which is cool.

And there's that sense of you being a little bit vulnerable and reaching out to people, like you mentioned on your social media about the vocal coach that you had to meet with, and reaching out to Liz Vice out of nowhere and saying, "Hey, can we collaborate on this?” There is a vulnerability that comes with that when you are not in control.

Yeah, totally, totally and I think vulnerability is a good word for that whole process, because with spoken word I've been doing my thing for a while, So when I record a spoken word album or project or song, I have so much confidence because it's tried and true. It's like, "I know I'm good at this". But with blues it's like, dang. It's not that I think I have a terrible voice, [it’s just] I don't have a tired and true voice. I've never done a tour. I've never put out an album before. So I don't know, and it’s scary. For the first time in a long time I'm in the studio feeling nervous, like is it good enough? I'm taking 20 takes of every song because I’m nervous. So it was crazy for me to see how much that affected my performance, even in the studio. Being relaxed is the most important thing, Because I know I don't have a natural Usher, or Michael Jackson R&B voice.

Blues is about channelling the right emotion. And some of the best blues vocal sets have these real kinda gritty voices that might sound a splatter off-key sometimes, but for the genre and the things they have to communicate, it’s perfect. Because, again, it was birthed out of the black community during a time when it was pain. It's pain, and they are singing about poverty, and they are singin about heartache, and they are singing about facing prejudice, and so that [doesn’t result in] a clean, neat sound.

At first I was trying to sound good. And then I was like, no, I don't need to sound good. I need to channel the right emotions. As a spoken word artist, I have a lot of experience channeling emotions into performance. So when I thought about it like that, I was like, okay, I need to relax and realize that if I connect emotionally to these songs, my voice would do what it needs to do. I can’t do what I'm not capable of. I can't sing real pretty, but that's not what I need here. And so I begin to relax and trust myself. And a lot of that had to do with having the vocal coach, and having Blaine tell me, "It sounds good, calm down and just do your thing, trust yourself.” So yeah man, it was very, very vulnerable being in that place of not being sure if it was going to be good or if I was good enough to do this. I'm glad I challenged myself in that way.

You mentioned how the songs are more - you mentioned chanting, repetition, simplicity. I have a friend who says when you write a short story you use a lot of words, whereas when you write a song you are compressing it into into very few words, which is a way bigger challenge.

What did this medium of blues allow you to say that you wouldn't have been able to say if you had not used it?

Oh absolutely. Not only what I'm saying but how it is being received. For example: if somebody sees me perform spoken word, and likes it, and buys the album, you can listen to it on the regular all you want, but you don't really participate in spoken word. You just appreciate it. You watch it. But with blues, like you were saying, with music in general, but particularly the blues is repetitive at times, like "I don't pay no mind" over and over again. What it does is it washes over the listener in a way that spoken word or hip-hop [doesn’t]. A lot of folks like hip-hop, but it's not as easy to pick up all the words and to rap along, right? But with the simplcity and reputation of blues, I'm like “man, the things that I say people are going to singing them in the shower. People are going to be playing them in the car on your way to work and on your way home. People are going to get them stuck in their heads and are going to be humming them while they are vacuuming and cleaning their house.” That's very different from someone who listens to a spoken word piece or watches a spoken word. They may be super impressed by it and like it, but it doesn't really get stuck in their heads and they don't sing along.

It made me think; what are the messages that I want folks to have on repeat in their heads? Like, what are the choruses that I want them to be singing over and over and over again, the truths that I want to be washing over their minds and hearts on a regular basis? That's the responsiblity! And so I love that. I love that people are walking around singing that they're not going to let themselves be overcome by hate. I love that. I love that people are walking around singing that “I'm not ugly.” “God ain't gave me no ugly babies.” “I'm handsome, I'm pretty, I'm worth, I look, I look good, I look good, I look good”, you know? [Laughs.] Those are the things, like [starts singing]; “I look good, ma, you look good!” That is a repeated, intentional phrase, like, tell yourself this over and over and over again. God made me good. He made humans and said it was good. And there is beauty in who we are, in addition to our brokenness, of course. So it’s things like that that a allowed me to communicate in a way and using qualities that the other genres I had written in didn't really possess.

I would say that spoken word lures you in and kind of shocks you. And blues does too, when you realize what it is saying. But I’m not going to put a spoken word album on repeat.

No.

You sit down and listen to it. Whereas with this, you play it while driving around.

What would the consequences have been if you had kept yourself in the comfortable medium you were used to?

The thing is, if you don't try stuff that is different than you are going to become a one trick pony. You are going to get stuck. Yeah, you can always come back to your home base and the things that you are known for, but I look at every major artist that I respect, and they were constantly pushing themselves to the limit. You don't know what you can do unless you push yourself and do stuff that you can’t. If we're talking about business here, if we're taking about having fianicnal success as an artist, [then recording this blues album] was a poor investment.

I have spent the last four years building up a following for spoken word poetry. All of my invitations are for venues and events that want a poet, not a blues artist, not a blues band. Nobody knows me for that. I’m starting from scratch. But the thing is, my aim was never to build a successful spoken word business. My aim was to express myself through the creativity that God has put inside me. I know that it is easy to stick to what is already tried and try. But I think about spoken word and how that was a risk. For two years people liked my rap and they were booking me for rap. If I were to just stay with that - and I had been listening to hip-hop from birth. So it felt familiar, it felt very at home. Poetry was foreign. This was - oh this was new, spoken word was a weird thing. But I’m like man, if I had only stuck with what was safe, I would have missed this beautiful aspect of what I’m capable of.

So I always want to be pushing myself. And that doesn’t always necessarily mean a new genre as drastic as this. One thing I’ve been trying to do lately - I do a lot of storytelling, [but] I don’t use use a lot of metaphors. I don’t use a lot of imagery or extended metaphors, because I like straight-up storytelling. But I’ve found recently a couple times, while listening to my friend’s words, I’m like, “Man.” I somethings resent metaphor a little bit because I think it’s overdone and people make it really confusing, they stack metaphor on top of metaphor and you don’t know what they are talking about . But when it's done well, it really does enhance understanding and makes it beautiful. So I’m challenging myself as a writer, [because] storyline is easier for me. But how can I write poetry that uses metaphors that enhances comprehension rather than make it more convoluted?

I do think that’s possible. I do think a lot of times poets hide behind the metaphor and they abuse metaphors. Because, yeah, I think the intention behind metaphor is that you have something you want to communicate and you doin’t quite have the words for it in plain speech. So you liken it to something in culture or in the world that your audience is familiar with so that it better resonates with the person, so that they comprehend it even more, rather than less. And what happens is that people use it in a way that folks don’t understand it.

But I think about the Psalms and here you have David, who grew up as a shepherd boy, and was very familiar with shepherding, and the culture he lives in is very familiar with shepherding. And so when he sits down to write a song or a poem about his relationship with God, he goes, “You know what it’s kinda like? It’s kinda like a shepherd and the sheep. You know how a shepherd takes his sheep and leads it to green pastures and he protects it and he restores it and he puts it by the river and make sure it drinks… that’s like… the Lord is my shepherd. That’s what it’s like.”

To me, that is how metaphors is supposed to be used. He’s speaking to a culture that’s familiar with these things. So they listen to it and they. “Oooh, okay.” That's a metaphor that enhances understanding, instead of making it more convoluted. And that’s something that I do appreciate when its done well. And so often poets, particular, try to be so deep, that it’s metaphor on top of metaphors, and I'm confused, I don’t know what you are talking about. But now I'm like, you know, I don’t want to throw the baby out with the bath water, so I'm pushing myself to engage with metaphor and extended metaphors that will both beautify my writing and enhance comprehension.

Because sometimes a metaphors does work better than saying it straight up, when you liken it to something, and folks are like “oh, now it’s connecting the dots.” Which is why preachers use it all the time for sermon illustration, because if they had just said it straight up it wouldn’t have driven home like likening it to something would have.

You mentioned earlier about pushing yourself and making yourself vulnerable in the new medium. Art & Fear talks a lot about that; the fear of failure and the fear of quitting that comes from that. Were there times when you were tackling this new medium, that… Maybe because I’m a younger artist, but my identity gets so caught up with my success. When I think that my writing is turning out to be successful, I’m thrilled, but when I think it isn’t worth it, then I just start to question everything. What was that process like during this new art form, especially as a believer?

Yeah. Let’s go into Art & Fear. The last part of the question, [about] the new art form; a lot of the reason I was able to approach it this way was from the things I learned from reading Art & Fear a few years ago. I didn’t have a deadline. I knew it was something new. And it took me two years, two full years to write and record all this stuff. I had no deadline. I knew that I ddin't know what I was doing. I knew that it wasn't going to be good right away from the first time, [from the] first draft. I knew that we were going to have to go back to the drawing boards a lot. So I gave myself the freedom and the time to create without going, “oh it’s not working.” No no, I’m trying something new.

And when you are trying something new you have to be patient with yourself. You don’t expect it to be amazing. You’re figuring it out. And [for] the whole album I was figuring out my sound. It wasn’t until about half way through, so about the 5th or 6th song, that we hit any type of stride in finding the sound we wanted. So the second half of the songs [that] we recorded were great. But once we finished those, we went back. There were three songs in particular that [we] completely started over [with]. Like, threw out all the music we had and approached it differently. Because we didn’t hit our stride until half way through.

But I guess to me, I already knew that it wasn’t going to be amazing right off the bat. That we had to figure it out slowly, and [the reason] I knew that [was] because of Art & Fear, really. And this is why [the book] is so influential with me. For me the premise, like, the repeated theme in the whole book was "no matter what type of artist you are, no matter how good or bad you think you are, most of what you do is going to not be good. Most of your work is going to suck.” And there’s a line in it where [they] say. “what the artist needs to understand, is that the purpose of the vast majority of your work is simply to show you how to create the small portion that will be good.” And that, to me, that freedom to create knowing good and well that even the best artists in the world… It’s so arrogant to think that every time I pick up my pen every single poem or song I’m going to write is going to be brilliant. Every time this person picks up his brush it’s going to be a classic. Every time she opens her mouth… That’s so unrealistic! And it’s so much pressure! So that book helped me realize to just fearlessly create. In the sense, when you get ideas, just get them out. Just create them. They are not all going to be good. In fact, most of them won't be good.

It was Art & Fear, and also a few other things that I watched. Like, I ended up watching a documentary on Pablo Picasso, I believe it was. By the end of his life was incredibly wealthy, he had his pictures hanging for half a million dollars in museums and all these things. But, when he died he lived a mansion that was like three or four stories high and had a basement, and they went into his home and all along the walls of his basement, stacked like 10 canvases deep, all along the wall was just canvas after canvas of mediocre, not that good, paintings. So for every brilliant Picasso painting hanging in a museum there were like 10-12 canvases in his basement collecting dust that he thought were not even good encough to share, but [that] he still painted. And so that's how I feel about song writing, or poetry. No matter how good I am, 8 out of 10 are going to be either mediocre or bad. So if I let that discourage me, I’m just not going to have a lot. But if I let that say, “Hey I don't care, I'm just going to create” and I write 100 poems, I’ll have 80 bad poems but I’ll have 20 good ones instead of just the two.

So it’s kinda like that. I just I let myself create. I try to get the the ideas out and not put the pressure on me not being good. That helped me not put the pressure on the album. I took my time and I was proud of it in the end.

What does that look like in the social media age, in which every artist has a social media account and can post a photo right away, or the idea right away? It seems harder to guard against that.

I think that is a huge temptation of immediacy. Whether it’s a song or a poem. Especially if they like it, which might not actually mean it’s good, because a lot of times artists have a personal connection to their work, that other people… Like, you love this but it’s actually not your best work. But there’s this temptation to share immediately. And I get it, because when I write something that I like I want to show the world.

But sometimes it needs time to develop. Sometimes you can share prematurely. If you’re posting singles the whole time you’ll never get around to posting the album and, when you do, everything will be out already. Sometimes if you’re posting every poem you write, by the time your book comes out nobody’s going to be excited because they’ve seen it all already. And I think if you have the displine to to hold some things close to your chest and let them develop and be refined, that’s definitely something that I’ve had to learn to do. Even with the blues album, there were so many times in the studio where I loved it, and I wanted to post clips to the song and it I was like, “No no, just wait, just let it be.” But yeah, it’s not an immediate thing. It takes a lot of time. No matter what your art form is.

I think people are impatient. I meet folks who want to be an artist or a singer or whatever and they have this incredibly unrealistic timeline in their heads. Like okay, I’m going to quite my job, and I’m going to work really, really hard for like 6-9 months, and if this thing isn’t off the ground in a year then I’m going to go back to my full time job. And I’m like, “Do you understand? I am four years deep and [am] still unknown.” And I don't resent that, because things have grown. But, by and large I'm a no name artist. I’m not selling out shows. I can't book a venue. You saw me. Going over to my homegirl’s back yard and reading three poems for 15 people. But, I’ve also had some opportunities for bigger stuff, but [over all it’s been a] very slow and gradual process.

And very few people… I know that’s the narrative that TV and media shows [emphasize}, the artist who gets discovered and boom, [becomes] an overnight celebrity. But when I look at the artists that I respect the most and whose work I really appreciate, I see years. [So] don't think about where you want to be in 1 or 2 years. Think about where you want to be in 10 years. 10 years as an artist.

When I look at artist like Josh Garrels, when I look at artists like Propaganda, even still these guys aren't celebrities. But I love Josh Garrels’ music and he has a sizeable following right now. When you look at him though… I wasn’t familiar with his work until ‘Love and War and the Sea In Between’ [came out]. So I’m like, “Oh wow, this album is amazing.” And I loved it. Well, to me, in my head, he’s a new artist at the time when that [album] came out. Well, I look him up, [and] the dude is not new. At that time he had had several albums out. He had been making music for a decade. And he is still, to this day, relatively unknown. He has a strong enough following to support himself. But he is by no means as big as a lot of artists, especially those who are talking about faith.

And yet, the funny thing was I love, loved, ‘Love and War and the Sea In Between’. But then I listen back to his other stuff and I liked it, but I didn’t love it nearly as much. And to me, that wasn't a bad thing, that was encouraging. I was like, “Wow, I can actually hear the difference between something you put out today and something you put out three years ago.” He’s grown. And he’s continuing to take risks and do different stuff and so I love the fact when I see his career it has been gradual, incremental progress. And that’s encouraging!

Because I think about me. I’ve been a full time artist for four years. At this point, with “No Ugly Babies”, this is my 5th release. I have two full length spoken word albums, one full length blues album, and two 5 track hip-hop EPs. So in 4 years I’ve released 5 things. All different. [For] most people who discover my work it’s new, and I'm new. I have [only] 3,000 followers on Instagram. I want to do a full length hip-hop album in the next couple years because that [medium] was my first artwork. So in the next couple years, as things continue to grow folks [will] continue to discover me as this new artists.

No, I'm not new. Whatever I make next year, and the year after that, and the year after that, has all been possible because of these gradual steps that I have been making and pushing myself. That is, to me, [what] successful artists do, by and large, with the exception of a very few who get the right connection and shoot to the top. [For] most successful artist, it is like that. It’s the tortoise verses the hare. I’ve seen it over and over and over again.

And people look and they envy the success and they go, “I want to be there, I want to have what you have. Man, Micah, you’ve been able to travel the world, you’ve been able to do this and do that.” And I’m like: “Yes.” But, I also ate cereal for dinner for the first two years, and I have also invested $15000 of my own dollars on making a blues album. That’s a huge risk. Are you willing to take literally half of your annual income, and invest it in something that might not make you any money? If you are, yeah, maybe you want this life. Are you willing to wait for four, five years, to have some of the opportunity you were hoping to have? Are you willing to make decisions financially and sacrifice some of theses habits of shopping and eating and doing things in order to do that?

I don't feel like a staving artist because I make financially wise decisions in order to do the things that I want. Like, I have everything I need, but from the car that I drive to the place where I live [I’ve had to make sacrifices]. I have 5 roommates in the house so I can have cheap rent. Because when I keep my expenses low I can invest more of my resources into making the art that I want.

So I just think there are a lot of illusions as to what it means to bean artist and most of it is not glamorous. But then when people see that I’ve got to perform for NBA teams they think I made it. When people see that I went to New Zealand or India or Paris, they’re like “Oh, your famous!” And I’m like, “Nah, this is the result of a lot of hard work, and even still I’m not there. There is no arrival. I’m just continuing to create.”

The book talks a lot about out about failure and pushing on. It’s interesting looking at that and then looking at it as a Christian, who’s identity is beyond just the art he creates. What would you add to it as a Christian that you would encourage other arts who are Christians, especially looking at the sense of failure and identity?

Honestly, part of the reason I love the book is because I thought it was so applicable to the spiritual life. They authors didn’t know it, but they wrote a devotional. People want that same kind of instant success when it comes to spiritual growth and spiritual health, and ministry, and God's will. People think being a mature, having a healthy relationship with God [is immediate]. It takes discipline. It is a slow but sure step-by-step gradual increase in maturing and that comes from just disciplining yourself. And you know what? You're going to make a lot of bad discussions. You going to make mistakes, you’re going to do things and create things that don’t work, but when you do, you keep going, you keep trusting God, you don’t let your failures discourage you. You dust yourself off, you receive the forgiveness, and you push on.

And so I was taking all of these principles they talk about as an artist and applying them to my spiritual life. I’ve done so many things, just like I’ve written so many poems that I though were going to be good and just fell flat. I’ve made so many decisions in life and spirituality, [thinking that] God wants me to do this, and I’m [being] led to do this, and it just crashes and burns. Are you going to throw your hands up and say you’re a bad Christian? Are you going to throw your hands up and say God is done with me? Or, are you going to say, “Okay, guess that’s not what God wanted, let me do something else. Let me not loose hope.” And that’s what people do. They just throw their hands up and say, “This is too hard, life is too hard!” And I’m just like, “Nah, remind yourself of why you are doing it, know that it’s worth it no matter what, and know that you are growing in all the things that you do.”

And even the aspect of them talking about not finding your identity in your work. They are like, “This is a modern thing but there’s been a lot of times in the past when artists would create and that wasn’t their soul. Like, if you don’t like my art, you don’t like me.”

That also is applicable to the spiritual life.Because there’s a lot of people who find their identity in the things they do for God. People in the ministry - and for me, it’s one and the same, because it’s my art, and then also I do see my art as the words of God and God using that. But it’s not who I am, it’s still something I do. And I’ve put a lot of vulnerability, and I’ve put a lot of myself into my art, but my art is not me. So whether it’s the things that you’re doing, whether it’s justice work, or in a formal ministry like working for church or for a youth group. It’s like yes, God is pleased with those things, but God does not love you because of those things. He is is not pleased with you because of the things you are doing.

In the same way as an artist you make beautiful art, but you can’t tie your identity so strongly to it that you are going to be depressed because if people don’t like your art then they don’t like you. And same thing with ministry. If you’re trying to do things for God and it’s not going well and no one is being converted, or the ministry isn’t growing, then you’re going to feel like a personal failure or that you’re not a good Christian. So I just made all these connections reading that book. “This makes so much sense. This is a devotional.”

There’s a line in the book where they talk about how “every artist will leave a thread loose in their work that they can pull on later.” Meaning that if you are working on a great piece of art and you’re exploring these themes, you’re going to leave a thread that you are working with that you want to unravel in your next piece of work.

Oh totally. Because there is no completion. I’ve found it to be a funny thing, that with any project I’m working on, by the time I’m approaching the end of it I’m already thinking of the next one. Because you learn so much in the process! You’re like, “Man, by the end of this album, if I were to start this album today it would sound very different.” But I don’t have time to start all the way over. I have learned so much in this process that although I’m done it feels like I’m just getting started. So it feels incomplete always. I kinda kinda feel that way, that the creative process is such a stretching and a growing thing that I’m always thinking about this process and how it [will be different] the next time around. And you don’t want to have a sense of, “Oh, everything’s done, there goes all my creativity.”

Are there any themes that you’ve talked about this time that you want to keep going with?

Yeah, definitely. Because of everything that’s going on in America, I want to continue to explore themes of black history, and culture, and presence, That’s something I want to be intentional about. Issues of justice in general have always been a theme in a lot of my work. Just because of this moment in time.

But then also more specifically even in that, the concept of loving your enemy has been so heavy on my heart because there’s been so much division. And rightfully and understandably so. I’m not about “Kum by Ya”, can’t we all just get along. I’m like, nah: these fools are my enemies. A lot of things people are doing and saying in my country right now, I am pointing out, that they are my enemy, they are my enemy. The things they are promoting, the things they are speaking are evil and anti-black and anti-peace. And so just being in a context of, “Okay, I have to recognize these folks as enemies, so what does it mean in this modern context to generally love my enemies?” That’s a difficult thing to think through, what that means.

Here’s the last question I want to ask you: this moment in American history is fascinating and scary. But in the sense we and my friends, who are white guys raised in Canada, are starting to be more aware of what that means and what the identity of the white evangelical has been through that journey. So whether it’s films like 13th, or your work, or Propaganda, or Sho Barka, these guys are coming into our lives and really waking us up.

But as Canadians, it can very easily be the temptation to look down and cast judgment, or even sit back and wait for the fireworks to begin. Because our history and our identity are so different. And yet the sin of racism applies to all of us. So I’m curious: you’ve spent some time in Canada. What would you say to people like myself who are maybe waking up to these themes, but who are white and are not American?

I think Canadians - and I say this with all respect - but I think they are very blind to their prejudice. Because on the surface level they don't have the same ugly history - although they definitely have some of it towards the indigenous people and the First Nations - like especially towards black folks and immigrants. You guys are a lot more welcoming of immigrants and you don’t have the history of slavery. So there seems to be this superficial, “We love people and especially more than Americans do. I mean look at those people down there!” But, particularly within the realm of theology, Canada is just as bad as America and doesn't realize it.

Because without realizing what Evangelical Christianity has been, particularly white evangelical Christianity… I have that’s about walking up to prejudice in the church. One of the things that comes up… I went to Bible college, and it was a predominantly white Bible college, and I was talking to one of my buddies who was Jamaican, a black dude, and he was like, “This is hard, because I come from an all-black community to this all-white community.” And he goes, “My roommates are white and my professors are white.” But then he said something that stuck with me and I’ve been thinking about it [still], years later. “Even all of the authors of the textbooks we use, they were all white.”

And a couple years after BIble college I was thinking about that conversation, and I realized that - because of Bible college I developed a love of theology and philosophy - and I had the realization that every single book of theology and philosophy that I had ever read was written by a white male. And I thought to myself - how ridiculous is that? The church of Christ is so broad. And yet when it came to my thoughts about God, theology, and the things I’m learning have all been taught to me by one slender slice of the human family and one slender slice of the body of Christ.

And the thing is in most evangelical circles that’s true of both our literature and our teaching in church. Most of the time churches are pastored by white males and leadership is predominantly white male. And so the books we read, the leadership, but then also the songs. Like most songs sung by churches are by Hillsong or Bethel Music, or [other] white contempary Christian music artists and worship leaders. Again, you are missing out on such a rich history. I say it like this because people tell me, “Why should this matter if we are all preaching the same Gospel.” [And I say]: because all of us, our cultural experiences inform our perspectives. And I’m not saying white guys don’t have good things to say. I’m not saying that. But [compare] a white guy talking about a concept of freedom, verses reading the literature of a black American slave who is writing or singing about freedom. Because of the Gospel, that takes on a whole different and deeper meaning.

In that same sermon I talk about how I had the chance to go to Hong Kong [where] I listened to a Filipino woman, who taught at a seminary in the Philippines, talk about prayer. And the thing is, she wasn't the most articulate or the best person I’ve ever heard speak on prayer; however, she was the most Asian. She talked about how in the DNA, in the roots of Asian culture across the board, they have practices like meditation, like yoga, like tea time, like they are used to sitting in silence and listening to God. So when their ancient cultural practices that are known in their ancient culture come in context with the gospel of Christ [it results in] something beautiful and particular. No matter how intelligent a white guy it is teaching me about prayer, he does not have that cultural lens.

And this is apart from the church and even in culture. I [ask] folks: what is white privilege? [And they respond} “What do you mean? You guys can eat at the same restaurants and go to the same schools.” Look, especially with Barack Obama becoming president, it [has] almost annoyed me, not because of his politics but because, for a lot of people in America, for them it was the symbolic end of racism. “Look, you can no longer complain because a black person is holding the highest office. Look, he’s made it.” And obviously, the election of Donald Trump has proved that otherwise. But at the time, it was like, “Look, we’ve made it.”

And I say no, listen: Obama is a freckle on the white face of American politics. You need to look at not just the presidency, but you like at Congress, and you look at Senate and not just politics either. Look at any major institution in America. Look at big business, look at higher education, look at medicine. You rise to the top and you look at positions of power and influence in any pillar of society and overwhelmingly, by and large, it it is white and male. Even if people were not intentionally skewing the policy to benefit their own people group, when you have such a drastic imbalance it is going to naturally affect [society]. Imagine… American politicians [are, say], 90% white and male. Imagine it it was 90% Latino women. Now, tell me that would not have an effect on the policies [on which] America is run? Or black women. Or Asian men. If it were 90% Asian men in that position of power, things would change even if they weren’t on purpose trying to affect their people group.

So that happens in culture, and Canada is the same way. You might have a diverse group of folks, but in the pillars of society, who holds the position of power, who has the money and the influence? It’s white dudes. And in the church in Canada a lot of your theological resources are the same that Americans use. Don’t get me wrong. I love Charles Spurgon. I love C.S. Lewis. I love A.W. Tozer. I love all these old white guys. They have taught me a lot. But man, I’ve been missing out on the black and Asian and Polynesian, and female theologians, and philosophers, and poets. I don’t even know who they are.

So for me, two years ago I started on a journey where I wanted at least the books I read to reflect the diversity. I want the books I read to reflect the diversity of the whole body of Christ and have influence from all of it. So I haven't read a book by a white guy in two years and I don’t plan on [doing so] any time soon. And it’s not all been theology: some, but I’ve read phisophy, I’ve read poetry books, I’ve read theology. And it has brought such a balance. So I think the Canadian church does’t realize that what [we are] interpreting as orthodox Christian theology is really white male theology. That’s all it is. That has a place, but it is not the place. It’s held up as [the normal].

I was just in Vancouver and I was talking to a guy who is Korean and he had a multiethnic church. His church is full of Koreans and Chinese and Japanese and Indians, but most of them are Asian even though they come form all these different cultures. And then they have a few white folks and black folks as well. He [told me that ] people will walk into his church and say, oh, this is an Asian church. But if you walk in to a predominately white church and there’s just a few minorities, you wouldn't say, “That’s a European church.” You’d say, “That's just church.” So that idea that white theology is not white theology, it’s just theology and then you have African theology and Asian theology, it’s not… it's European White theology, which is not bad. But it is not the standard. And that is the problem. The problem is that its’s been treated like the standard.

So when you talk about Christian history, most people are just talking about Europe. [Even though] Christianity did not just start in Europe, but spread through South Sahara and Asia and the Coptic church in the Ethiopian area is just as old as any European tradition, and you talk about Christianity in Latin American countries. We don’t talk about that.

And it’s the same thing in high school. When you are studying history, you are really studying European history because Sub-Sahara Africa has a whole history that we don’t talk about until the slave trade, because that’s when European feel into Africa. And you don't talk about Chaina at all, unless it’s the Great Wall. But you spend all these different times talking about European history and the industrial revolution. So what’s seen as world history [is actually} white history, and it’s the same thing with theology. What’s seen as orthodox theology is from Europeans and their descendants. That’s white Christian theology. That becomes destructive when it’s seen as the standard, when, if it’s approached correctly, it could be seen as a beautiful contribution to the body of Christ if it has its place

And a lot of times when i talk about this, folks are like, “Oh man…” Like one of my friends said, “iIsn’t that reverse racism to not read books by white people?” No. Because for the first 20 or so years of my life, I know all about that. Not to say I have nothing to learn, but it would take three more lifetimes to bring any type of balance. It’s like, by the time I die I guarantee you I will still have read more books by white culture, even if I never read another book by a white person. Because I don’t have 20 years to spend reading only Asian women and then only 20 years to spend reading only Latino men. It would take the rest of my life to bring any type of balance to this.

But just for me, when it comes to the books I read. But still, when I go around and travel and go to church's and meet people and watch movies, still white folks control a lot of the things that get the most exposure. So anyway, what I found in Canada that people don’t realize that. It’s like, ya’ll folks is white washed just like any other place in North American and Western European countries. You don’t read South American theologians and Asian theologians, you only read the white guys.

Well, thank you for your time. A lot of this applies to my life.

It’s very encouraging to hear, specifically how the blues album has meant so much to you. It was an experiment. I didn't know what was going to happen, so it’s cool to hear how much it’s affecting you.

It seeps into my life and makes a difference.